The letter came to the reserve collection of the Museum in 2016 together with the collection of British Russianist Gordon McVeigh — well-known scholar in the field of Russian literature of the first half of the XXth century and author of biographic books about Sergei Yesenin and Isadora Duncan, as well as multiple publications on the creative work and life of the poet.

Sergei Esenin wrote this letter in 1923 to imaginist poet Alexander Kusikov, who was a member of the ‘famous Moscow quartet’ together with Vadim Shershenevich, Sergei Esenin, and Anatoly Marienhof. ‘There were years, — Shershenevich recalled, — when it was easier to count the hours, which we — Esenin, Marienhof, Kusikov, and me — spent apart than the hours of friendship and dates’. The friends called Kusikov ‘court organ grinder’ as he ‘could edge himself wherever he liked to’ and ‘knew how to get on with everybody whenever he liked to’.

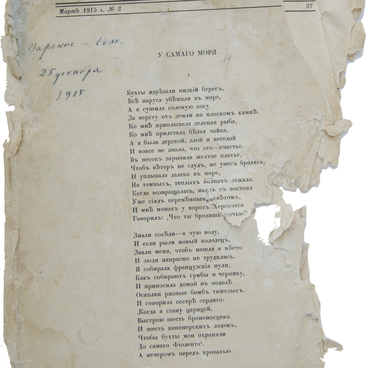

Alexander Kusikov got acquainted with Sergei Esenin in 1918, when the poet came to Moscow from Petrograd. Later he dedicated to the friend the Tavern Moscow cycle (1924) and the ‘Soul feels blue for heaven …’ (1919). Time and again Esenin called him ‘the last sole friend’ and was on friendly terms not only with Kusikov, but with other members of his family.

Sergei Esenin wrote this letter in 1923 to imaginist poet Alexander Kusikov, who was a member of the ‘famous Moscow quartet’ together with Vadim Shershenevich, Sergei Esenin, and Anatoly Marienhof. ‘There were years, — Shershenevich recalled, — when it was easier to count the hours, which we — Esenin, Marienhof, Kusikov, and me — spent apart than the hours of friendship and dates’. The friends called Kusikov ‘court organ grinder’ as he ‘could edge himself wherever he liked to’ and ‘knew how to get on with everybody whenever he liked to’.

Alexander Kusikov got acquainted with Sergei Esenin in 1918, when the poet came to Moscow from Petrograd. Later he dedicated to the friend the Tavern Moscow cycle (1924) and the ‘Soul feels blue for heaven …’ (1919). Time and again Esenin called him ‘the last sole friend’ and was on friendly terms not only with Kusikov, but with other members of his family.

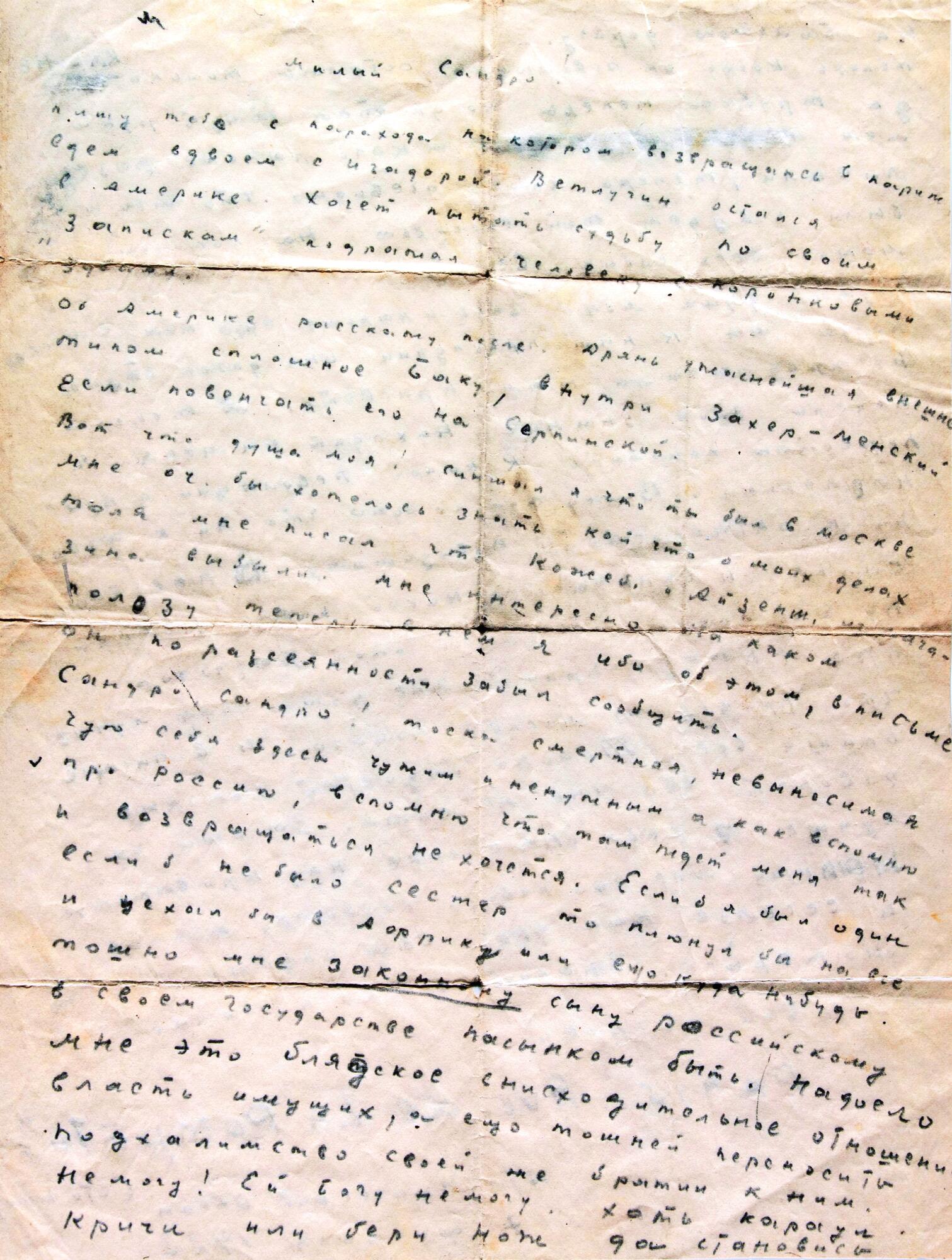

In this letter, Esenin writes to Kusikov from the steamer on which he is returning to Paris. At this time, the poet feels his separation from his homeland with great pain and at the same time is aware that he cannot find a place for himself in the new Russia. He is tormented by ‘wicked despondency’. ‘I cease to understand which revolution I belong to, ’ the poet writes.

This letter reflects the contradictory feelings that overwhelm him: ‘Mortal and unbearable longing, I feel a stranger and unwanted here, and when I remember Russia, remember what awaits me there, I do not even want to go back. If I were alone, if I didn’t have my sisters, I would give up everything and go to Africa or somewhere else. I am sick and tired of being a stepson in my own country. I am sick and tired of the condescending attitude of those in power, and I am even sicker of enduring the subservience of my own brethren towards them. I can’t stand it! By God, I can’t. I could scream bloody murder or take a knife and go on the high road.

This letter reflects the contradictory feelings that overwhelm him: ‘Mortal and unbearable longing, I feel a stranger and unwanted here, and when I remember Russia, remember what awaits me there, I do not even want to go back. If I were alone, if I didn’t have my sisters, I would give up everything and go to Africa or somewhere else. I am sick and tired of being a stepson in my own country. I am sick and tired of the condescending attitude of those in power, and I am even sicker of enduring the subservience of my own brethren towards them. I can’t stand it! By God, I can’t. I could scream bloody murder or take a knife and go on the high road.