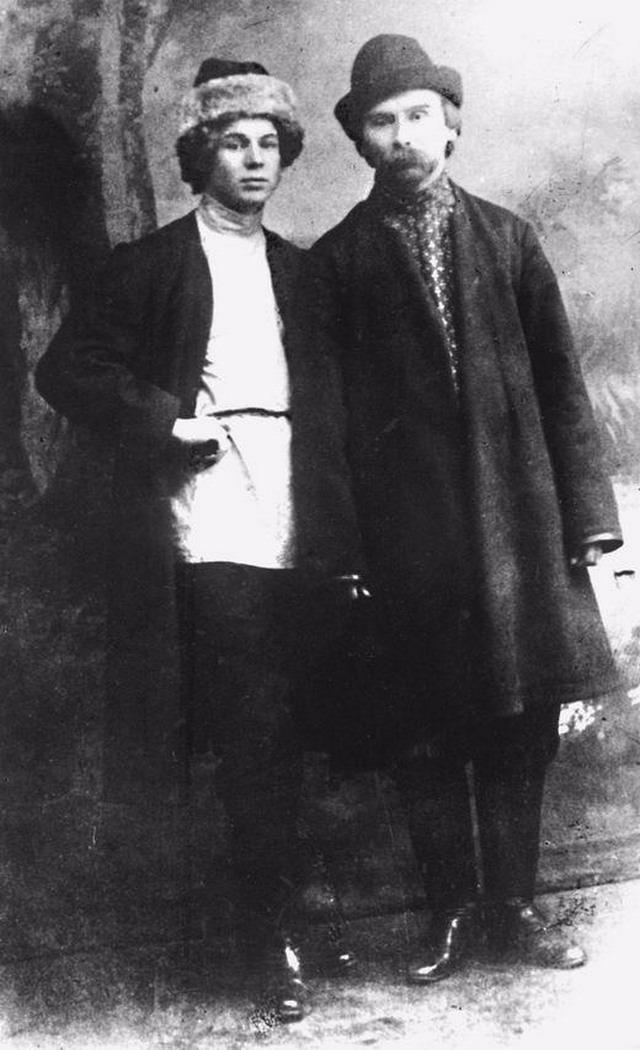

Sergei Esenin met Nikolay Gumilyov and his wife Anna Akhmatova in 1915: on Christmas, Esenin and his friend, poet Nikolai Klyuev, came to see the spouses in Tsarskoe Selo. Gumilyov signed his book of poems Alien Sky and gave it to Esenin, and Akhmatova gave him her poem At the Edge of the Sea. On the front title of the publication there is Gumilyov’s autograph, left in black ink: “To Sergei Aleksandrovich Esenin, in memory of the meeting. 25 December 1915. N. Gumilyov”. The book was kept in the archives of the poet’s sister, Ekaterina Esenina.

Alien Sky was published in 1912. Some of the poems in it were already familiar to the reader: throughout 1910 and 1911, they had been published in the Russian literary magazine Apollon. The book was warmly received by the audience.

Poet Mikhail Kuzmin wrote in a review: ‘To Gumilyov himself, the world around him probably does not seem young enough because he is more willing to turn his gaze to virgin lands. There, of course, it is easier to exercise the prerogative of Adam, who gave names for animals and plants… As a result of this desire, the poet either invents unknown animals (The Tamer of Beasts), then opens the tenth muse (Muse of Distant Travels), then gives the guardian angel a sister (Guardian Angel), then recreates Don Juan. This restless desire for the right to give names will only be satisfied when young Adam lowers his enthusiastic and too far-sighted eyes to the ground on which he stands, and it will truly appear to him as a new one, still waiting for its name.’

Anna Akhmatova recalled the day of her meeting with Esenin: ‘Apparently, it was on the second or third day of Christmas because he brought with him the Christmas issue of the newspaper Birzhevyie Vedomosti. A little shy, blonde, curly-haired, blue-eyed and utterly naïve, Esenin beamed all over as he showed the newspaper. At first, I did not understand what caused this radiance of his. It was his constant companion Klyuev who helped me to understand it, even though I didn’t understand Klyuev himself very well. ‘Why, dear Anna, ” he cooed – and yes this petty clerk cooed – breaking into a smile, his walrus moustache bristling, his eyes looking down for some reason looking down –, “my friend Sergei has been mentioned in the newspaper with all the noble ones, and even I am mentioned.” I couldn’t help but look in the newspaper. Indeed, almost all of our Petrograd ‘noble ones’, as Klyuev chose to name the poets and writers widely known at the time, was presented in the newspaper’s Christmas issue.

Georgy Adamovich recalled that, in the company of other poets, Gumilyov did not recognize Esenin’s talent: ‘Gumilyov immediately stated that Esenin was “simple and boring like two and two make four” and began talking ostentatiously whenever Esenin recited his poems…’

Alien Sky was published in 1912. Some of the poems in it were already familiar to the reader: throughout 1910 and 1911, they had been published in the Russian literary magazine Apollon. The book was warmly received by the audience.

Poet Mikhail Kuzmin wrote in a review: ‘To Gumilyov himself, the world around him probably does not seem young enough because he is more willing to turn his gaze to virgin lands. There, of course, it is easier to exercise the prerogative of Adam, who gave names for animals and plants… As a result of this desire, the poet either invents unknown animals (The Tamer of Beasts), then opens the tenth muse (Muse of Distant Travels), then gives the guardian angel a sister (Guardian Angel), then recreates Don Juan. This restless desire for the right to give names will only be satisfied when young Adam lowers his enthusiastic and too far-sighted eyes to the ground on which he stands, and it will truly appear to him as a new one, still waiting for its name.’

Anna Akhmatova recalled the day of her meeting with Esenin: ‘Apparently, it was on the second or third day of Christmas because he brought with him the Christmas issue of the newspaper Birzhevyie Vedomosti. A little shy, blonde, curly-haired, blue-eyed and utterly naïve, Esenin beamed all over as he showed the newspaper. At first, I did not understand what caused this radiance of his. It was his constant companion Klyuev who helped me to understand it, even though I didn’t understand Klyuev himself very well. ‘Why, dear Anna, ” he cooed – and yes this petty clerk cooed – breaking into a smile, his walrus moustache bristling, his eyes looking down for some reason looking down –, “my friend Sergei has been mentioned in the newspaper with all the noble ones, and even I am mentioned.” I couldn’t help but look in the newspaper. Indeed, almost all of our Petrograd ‘noble ones’, as Klyuev chose to name the poets and writers widely known at the time, was presented in the newspaper’s Christmas issue.

Georgy Adamovich recalled that, in the company of other poets, Gumilyov did not recognize Esenin’s talent: ‘Gumilyov immediately stated that Esenin was “simple and boring like two and two make four” and began talking ostentatiously whenever Esenin recited his poems…’