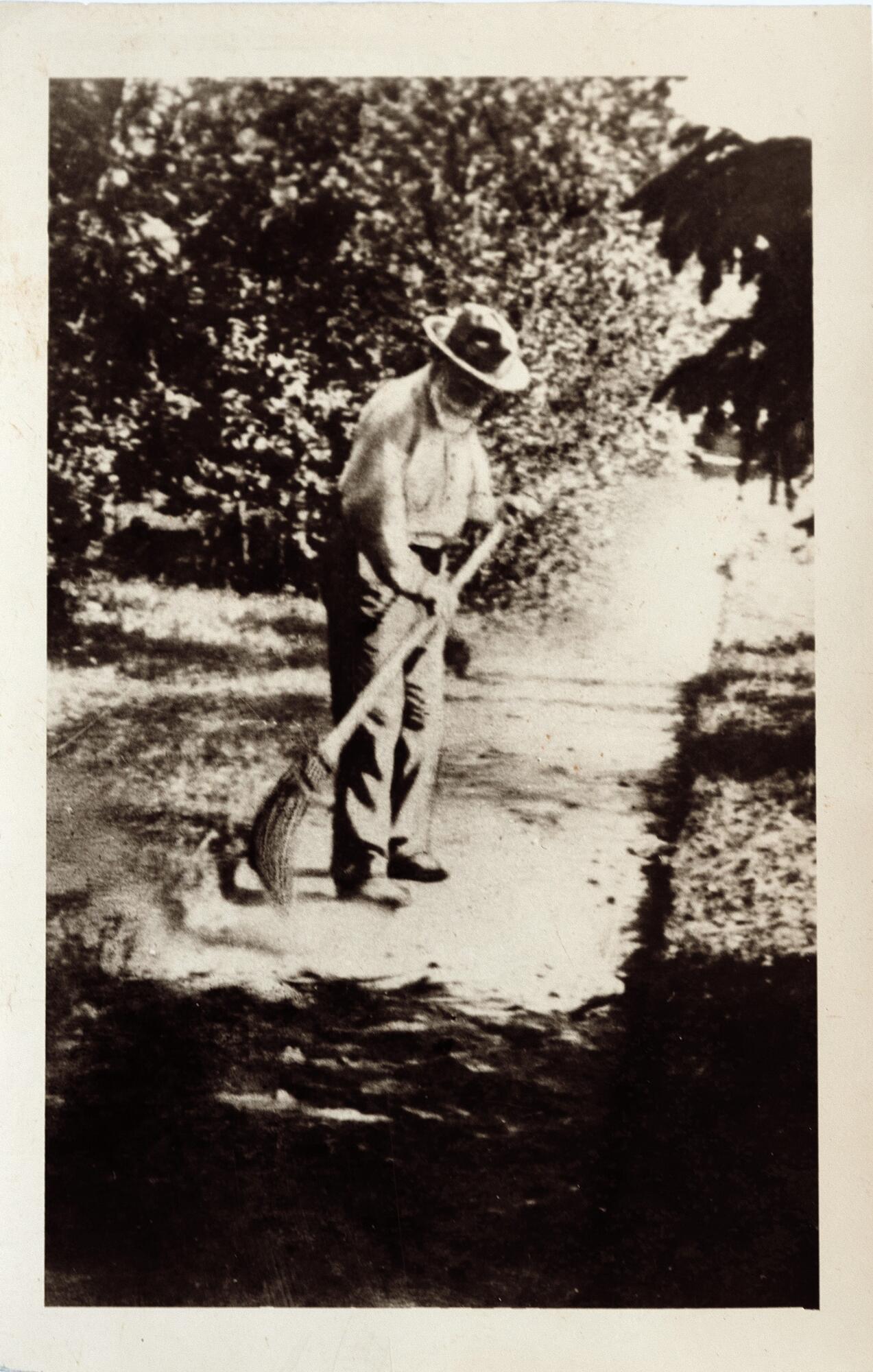

The academician Ivan Petrovich Pavlov was accustomed to labor from childhood. His father, Pyotr Dmitriyevich, believed that his sons should be able to do the same things around the house as he did. Father Pyotr taught the boys how to use tools, do carpentry and gardening. Ivan Pavlov called his father’s approach “an inoculation against idleness and laziness” and believed that it helped him immensely in life.

The scientist recalled how once the father decided to test the characters of his sons and instructed them to dig holes for planting apple trees. Ivan Petrovich remembered this day for the rest of his life. Ivan and his brothers had to calculate the distances between the holes with precision so that the young seedlings were arranged in a checkered manner. Vanya and Mitya worked in silence, their backs wet and breaths short, but the boys did not complain. Little Pyotr was entrusted with holding a large canvas umbrella over his father’s head and was proud of this elevated mission, albeit barely managing to do it.

When the holes were dug, and the boys were exhausted, the father realized that the distance between the holes was incorrect and suggested that the sons start over. Dmitry was in despair and almost burst into tears, while Ivan assertively picked up the shovel and set out for the garden. It turned out that the father was only joking, intending to test the characters of his children. Pyotr Dmitriyevich was pleased with his eldest son’s willpower and endurance. Ivan was the only one of all Pavlov’s children who inherited from his father the love of the land and dedication to gardening.

Ivan Petrovich Pavlov strongly believed that people need both mental and physical work for health and longevity. The scientist used to say, “The mind cannot work properly if you do not toughen yourself up with physical work.” The academician Pavlov’s wife, Seraphima Vasilyevna, wrote in her memoirs:

The scientist recalled how once the father decided to test the characters of his sons and instructed them to dig holes for planting apple trees. Ivan Petrovich remembered this day for the rest of his life. Ivan and his brothers had to calculate the distances between the holes with precision so that the young seedlings were arranged in a checkered manner. Vanya and Mitya worked in silence, their backs wet and breaths short, but the boys did not complain. Little Pyotr was entrusted with holding a large canvas umbrella over his father’s head and was proud of this elevated mission, albeit barely managing to do it.

When the holes were dug, and the boys were exhausted, the father realized that the distance between the holes was incorrect and suggested that the sons start over. Dmitry was in despair and almost burst into tears, while Ivan assertively picked up the shovel and set out for the garden. It turned out that the father was only joking, intending to test the characters of his children. Pyotr Dmitriyevich was pleased with his eldest son’s willpower and endurance. Ivan was the only one of all Pavlov’s children who inherited from his father the love of the land and dedication to gardening.

Ivan Petrovich Pavlov strongly believed that people need both mental and physical work for health and longevity. The scientist used to say, “The mind cannot work properly if you do not toughen yourself up with physical work.” The academician Pavlov’s wife, Seraphima Vasilyevna, wrote in her memoirs: