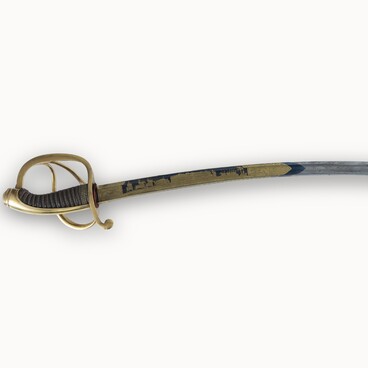

This exhibit from the collection of the Zlatoust Museum of Local Lore is a saber blade of the 1881 model, made of welded bulat (Damascus steel). It was decorated with the inlaying technique that was used at the Zlatoust Arms Factory only in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The blade was made of Damascus steel. According to the classification of mining engineer Pavel Petrovich Anosov, this is in essence artificial (or welded) bulat steel. It was obtained by the forge welding of plates of hard and mild steel. The bladesmiths used artificial deformation of the layers to obtain various patterns on the surface.

Pavel Anosov noticed that blades with mesh and angular patterns had better properties compared to other Damascus steel blades. Steel with undulated, curly and striped patterns was of worse performance. At the same time, such blades did not have the properties of real bulat and were mostly valued for their aesthetics.

This product, after forging and hardening, went to a department, where items ordered by private customers were decorated. The blade was adorned with floral ornaments. In this particular case, a certain technique was used, which became the most common for the Zlatoust factory in the period from the 1870s to the 1890s. The craftsman created inlays in gold and silver threads on a blue damascened background.

Damascening was inlaying made in three directions, so fine that the minuscule indentures covering the blade could not be seen with the naked eye. The surface was rendered a velvet-like texture. After that, the craftsman took a thin gold or silver wire and pushed it to the recess with a small hammer. Zlatoust artisans used not only convex but also deep inlaying. In the latter case, the craftsmen would cut the pattern with a tiny chisel and then fill the recesses with gold or silver wire, which was then hammered in.

Just two or three craftsmen at the weapons factory were skillful in this art; the work was very time-consuming and costly. That is why Zlatoust weapons made in the technique of convex or deep inlaying are very rare.

The blade was made of Damascus steel. According to the classification of mining engineer Pavel Petrovich Anosov, this is in essence artificial (or welded) bulat steel. It was obtained by the forge welding of plates of hard and mild steel. The bladesmiths used artificial deformation of the layers to obtain various patterns on the surface.

Pavel Anosov noticed that blades with mesh and angular patterns had better properties compared to other Damascus steel blades. Steel with undulated, curly and striped patterns was of worse performance. At the same time, such blades did not have the properties of real bulat and were mostly valued for their aesthetics.

This product, after forging and hardening, went to a department, where items ordered by private customers were decorated. The blade was adorned with floral ornaments. In this particular case, a certain technique was used, which became the most common for the Zlatoust factory in the period from the 1870s to the 1890s. The craftsman created inlays in gold and silver threads on a blue damascened background.

Damascening was inlaying made in three directions, so fine that the minuscule indentures covering the blade could not be seen with the naked eye. The surface was rendered a velvet-like texture. After that, the craftsman took a thin gold or silver wire and pushed it to the recess with a small hammer. Zlatoust artisans used not only convex but also deep inlaying. In the latter case, the craftsmen would cut the pattern with a tiny chisel and then fill the recesses with gold or silver wire, which was then hammered in.

Just two or three craftsmen at the weapons factory were skillful in this art; the work was very time-consuming and costly. That is why Zlatoust weapons made in the technique of convex or deep inlaying are very rare.