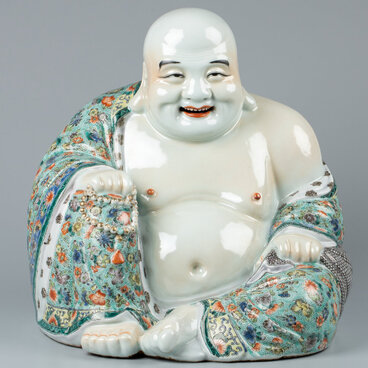

The Samara Regional Art Museum presents a magnificent porcelain figurine of a Japanese woman made in the workshops of Kutani. The woman slightly turns to one side with her head lowered as a sign of respect. She is dressed in a traditional kimono richly decorated with floral patterns and tied with a special belt called obi. The sculpture of the Japanese woman embodies modesty and elegance.

Pottery on the islands of the Japanese archipelago originated in the Neolithic period: the oldest artifacts are dated to the 10th millennium BC.

In the first half of the 17th century, the East India Company actively exported products made by Chinese craftsmen. However, due to the economic decline at the end of the Ming Dynasty, the Company’s work in China was completely suspended. Then the enterprising Dutch founded an office of trade representative in Nagasaki and replaced Chinese porcelain with the Japanese one.

Japanese potters succeeded in their efforts: both in Europe and in the US, the opinion was firmly formed that the Japanese porcelain was unmatched in technical execution and artistic quality.

One of the largest ceramic workshops in Japan were the workshops of Kutani. The term “Kutani ware” appeared at the end of the 19th century, 300 years after clays suitable for porcelain making were found in the Kutani gold mines (literally “Nine Valleys”, currently the city of Kaga, Ishikawa Prefecture, Honshu Island) in 1655.

The founder of the first Kutani pottery center was Goto Saijiro, a close associate of the head of the Maeda samurai clan. He studied the art of making porcelain in the town of Arita. Kusumi Morikage, the official painter of the Maeda clan, the famous artist of the Kano school, also worked on the design of the products. Today, art historians call such artworks Ko-Kutani (old Kutani). Ko-Kutani, in turn, are divided into the Aote type, which used bright enamels of dark blue, saturated green, purple and yellow shades, and Iroe, which combined red, purple, green, dark blue and yellow colors. The décor of Ko-Kutani ware was dominated by images of plants, birds, while the landscapes were complemented with abstract patterns. To protect the works from wear and tear, they were covered with transparent glazes over the enamel.

By 1730, the production of Kutani porcelain stopped and resumed only after 80 years. Over time, many adjustments in the technology and in the design of the products were made. Today they are commonly called Saiko-Kutani (literally “revived Kutani”).

Pottery on the islands of the Japanese archipelago originated in the Neolithic period: the oldest artifacts are dated to the 10th millennium BC.

In the first half of the 17th century, the East India Company actively exported products made by Chinese craftsmen. However, due to the economic decline at the end of the Ming Dynasty, the Company’s work in China was completely suspended. Then the enterprising Dutch founded an office of trade representative in Nagasaki and replaced Chinese porcelain with the Japanese one.

Japanese potters succeeded in their efforts: both in Europe and in the US, the opinion was firmly formed that the Japanese porcelain was unmatched in technical execution and artistic quality.

One of the largest ceramic workshops in Japan were the workshops of Kutani. The term “Kutani ware” appeared at the end of the 19th century, 300 years after clays suitable for porcelain making were found in the Kutani gold mines (literally “Nine Valleys”, currently the city of Kaga, Ishikawa Prefecture, Honshu Island) in 1655.

The founder of the first Kutani pottery center was Goto Saijiro, a close associate of the head of the Maeda samurai clan. He studied the art of making porcelain in the town of Arita. Kusumi Morikage, the official painter of the Maeda clan, the famous artist of the Kano school, also worked on the design of the products. Today, art historians call such artworks Ko-Kutani (old Kutani). Ko-Kutani, in turn, are divided into the Aote type, which used bright enamels of dark blue, saturated green, purple and yellow shades, and Iroe, which combined red, purple, green, dark blue and yellow colors. The décor of Ko-Kutani ware was dominated by images of plants, birds, while the landscapes were complemented with abstract patterns. To protect the works from wear and tear, they were covered with transparent glazes over the enamel.

By 1730, the production of Kutani porcelain stopped and resumed only after 80 years. Over time, many adjustments in the technology and in the design of the products were made. Today they are commonly called Saiko-Kutani (literally “revived Kutani”).