The tradition of decorating clothes, bedding and table linen with embroidery goes far back in time. In the old days, European needlewomen created unique embroidered monograms. They were inspired by manuscripts and books, and also borrowed letters that were stylized by famous painters. As a rule, embroideries for privileged persons were made more convex, various vignettes and threads of several colors were used.

Artists would embroider their initials on tapestries. In this way they protected copyright and made their name more recognizable. For this purpose, Gothic letters were used in Germany and England, and they were supplemented with decorative patterns. Swiss-style letters, which were embroidered in the technique of dense cordon stitch, visually similar to a roller, were notable for their openwork.

The first embroidered marks appeared on table linen around the 16th century. Dutch tablecloths and napkins of that time, which have survived to our days, have the name of the customer, weaver and even the name of the area where the item was produced. Bed linen, mainly in the homes of aristocrats, began to be decorated with lace and embroidery in the 18th century.

Later, the decorative finish became more complicated, and complex monograms appeared. For example, the initial letters of the first and last names were often intertwined in the form of a monogram, or conventional images of plants and animals.

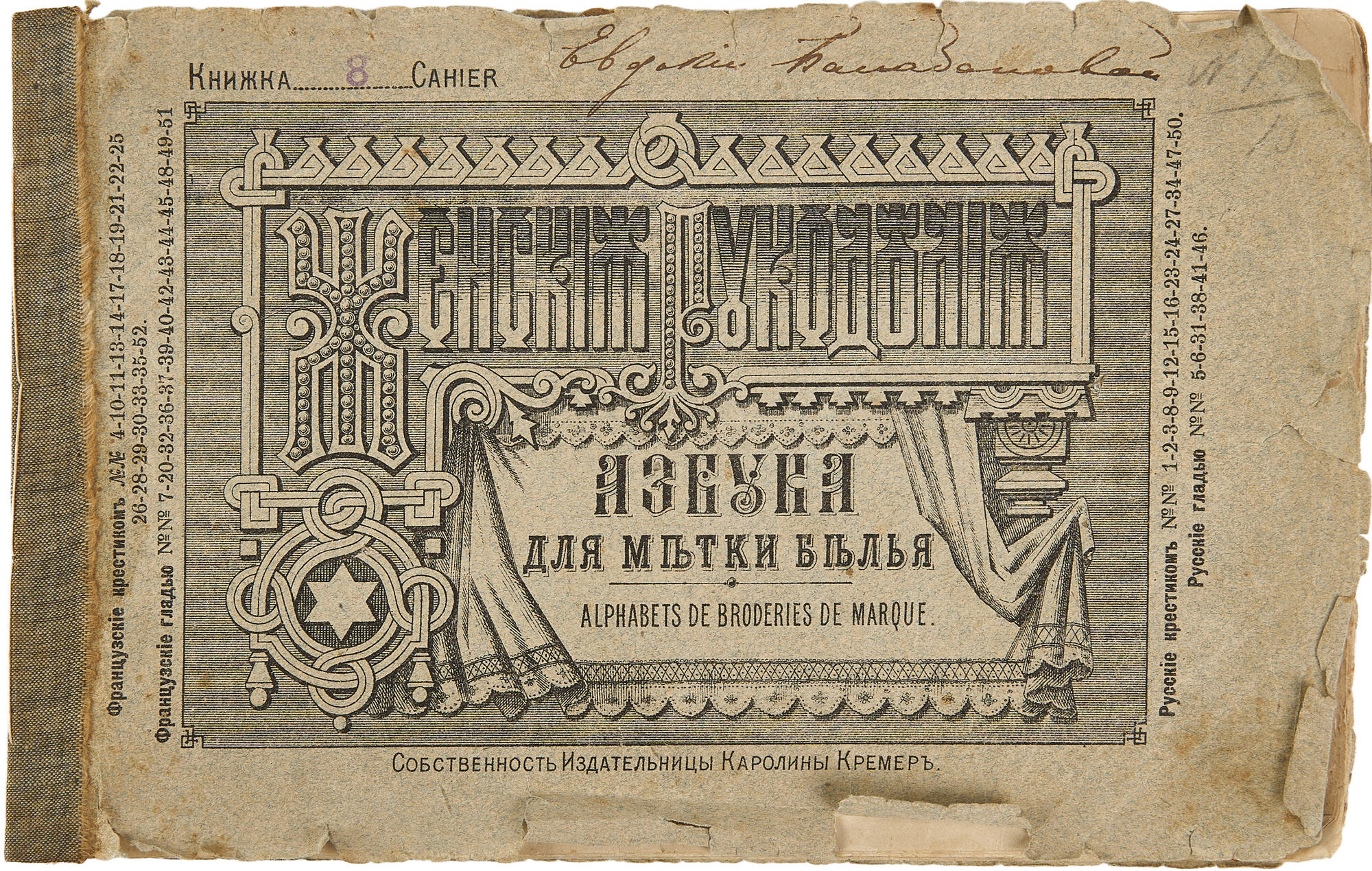

By the mid-19th century, embroidery and lace on

linen became popular in Russia too. Large dense white bouquets on the edges of

towels, sheets, pillow covers came into fashion. Tablecloths and napkins were

always decorated with a cipher, while in noble families — with a coat of arms

and a monogram. In 1846, the German educator Adelheida Mersierkler wrote in her

book “Entry of a young maiden into the world …”,